In 1939, Europe was burning. In America, most people wanted to stay home.

While German tanks rolled across Poland and Britain declared war on Hitler’s Reich, Americans watched from across an ocean that felt wider than ever. The isolationist mood wasn’t just political posturing: it was a deep, collective memory of what “European wars” had cost the last time around.

The Shadow of the Great War

Twenty years earlier, American boys had marched into the trenches of France believing they were fighting “the war to end all wars.” Instead, they found mud, poison gas, and casualty lists that stretched from small-town America to the industrial cities of the Northeast. Over 116,000 Americans died in World War I, with hundreds of thousands more wounded. The human cost was staggering for a nation that had entered the conflict late and reluctantly.

By 1939, those same communities were raising another generation of young men: sons and younger brothers of the doughboys who never came home.

The memory of that sacrifice wasn’t abstract history; it was empty chairs at dinner tables and Gold Star banners still hanging in front parlor windows.

Public opinion polls reflected this wariness. In September 1939, after Germany invaded Poland and Britain and France declared war, a Gallup poll showed that 94 percent of Americans opposed entering the European conflict. This wasn’t political calculation: it was visceral rejection of repeating the Great War’s trauma.

Fortress America

The isolationist sentiment had deep roots in American political tradition. For over a century, the United States had successfully avoided entangling alliances and European power struggles. Why abandon that proven strategy now?

Congress had already acted on this sentiment, passing a series of Neutrality Acts throughout the 1930s designed to keep America out of foreign conflicts. The 1935 Neutrality Act prohibited arms sales to any belligerent nation. The 1936 version banned loans to warring countries. The 1937 act extended these restrictions and added a “cash and carry” provision: if belligerents wanted American goods, they had to pay cash and transport the materials themselves.

These laws reflected more than just political philosophy. Americans genuinely believed that distance and neutrality could protect them from Europe’s seemingly endless cycle of war and destruction. The Atlantic and Pacific Oceans had always been America’s greatest defense. Why shouldn’t they remain so?

Roosevelt’s Tightrope Walk

President Franklin D. Roosevelt found himself caught between his personal convictions and political reality. Privately, FDR understood that Nazi Germany represented a genuine threat to democratic civilization. He had watched Hitler’s rise with growing alarm and believed that American security ultimately depended on Britain’s survival.

But Roosevelt was also a shrewd politician who understood the limits of public support. Moving too quickly toward intervention could destroy his presidency and potentially hand power to isolationists who might withdraw American support entirely. Instead, he walked a careful line, using his considerable political skills to gradually shift public opinion while respecting the constraints of neutrality legislation.

The president’s speeches during this period reveal his strategy. Rather than calling for war, he emphasized America’s role as the “arsenal of democracy”: a phrase that would become central to his approach. America could support the forces of freedom without sending its sons to die on foreign battlefields. It was a compelling compromise that honored both isolationist sentiment and interventionist goals.

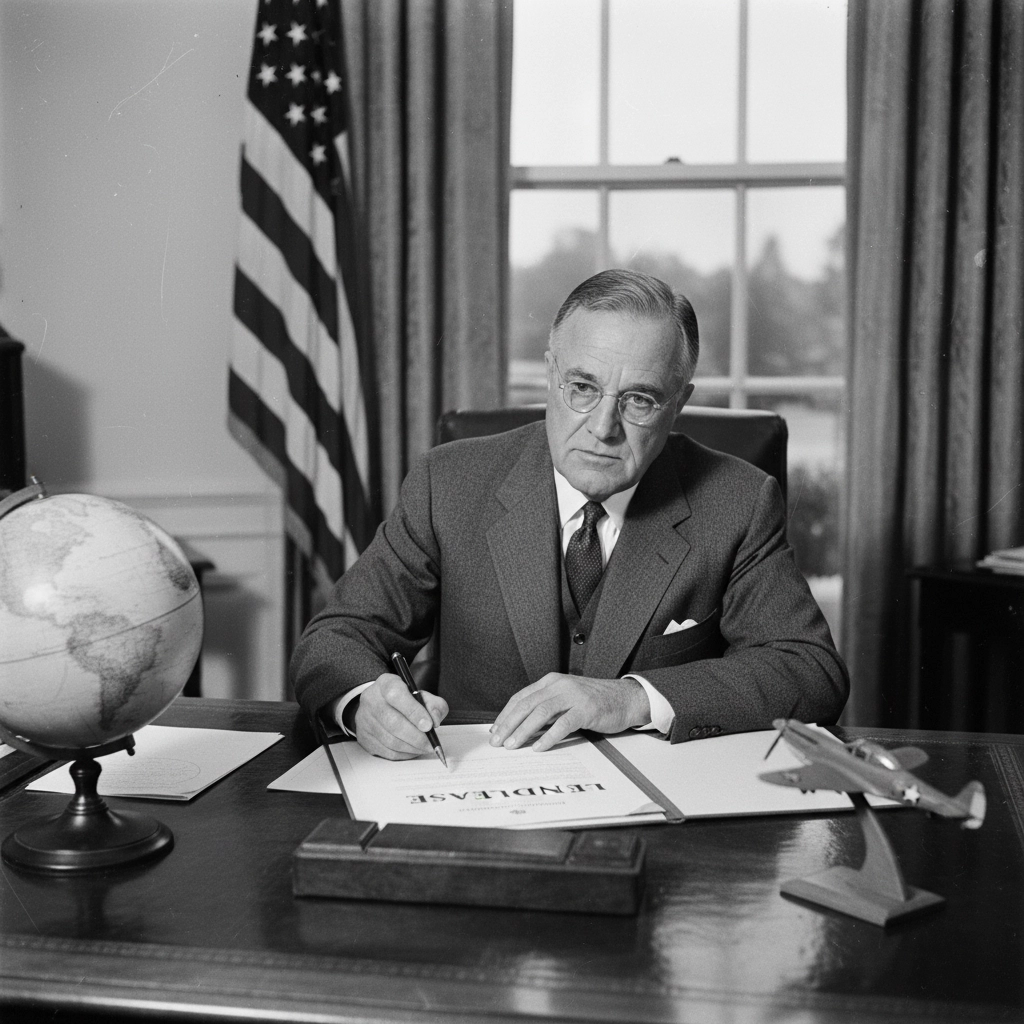

The First Crack: Lend-Lease

By early 1941, the careful balance between neutrality and support was beginning to shift. Britain was running out of cash to purchase American weapons and supplies under the cash-and-carry provisions. Without continued American aid, Churchill’s government might collapse, leaving Hitler in control of Western Europe.

Roosevelt’s solution was characteristically clever: the Lend-Lease program. Rather than selling weapons to Britain, America would lend them, with payment deferred until after the war. As FDR explained to the American people, when your neighbor’s house is on fire, you don’t sell him your garden hose: you lend it to him and worry about payment later.

Lend-Lease passed Congress in March 1941, marking a significant step away from strict neutrality. America was now openly supporting Britain’s war effort, even if American soldiers weren’t yet fighting alongside British troops. The program represented a crucial shift in American thinking: from isolation toward engagement, from neutrality toward alliance.

Training the Next Generation

While the nation argued over its role in the expanding war, a new generation of American pilots was quietly learning to fly the aircraft that would carry the country into battle. Flight training programs across the United States expanded rapidly, preparing young aviators for a conflict many Americans still hoped to avoid.

The pilots graduating from these programs in 1940 and 1941 represented a distinct cohort. too young to remember World War I personally, but old enough to understand the stakes of the new crisis. They trained on aircraft that reflected America’s growing industrial power. faster fighters, longer‑range bombers, and more sophisticated navigation equipment.

While the country debated neutrality and aid, these young pilots were logging hours in the sky. One of them was B.K. Watts, whose journey from stateside flight school to overseas combat lies at the heart of In the Slipstream. While this post focuses on the broader American mood before the war, In the Slipstream follows one of the young pilots trained in this period, B.K. Watts, whose own flight logs, squadron orders, and war diary document how that national shift played out from the cockpit.

Discover more about B.K. Watts’s journey in In the Slipstream: Read the book page

Leave a Reply