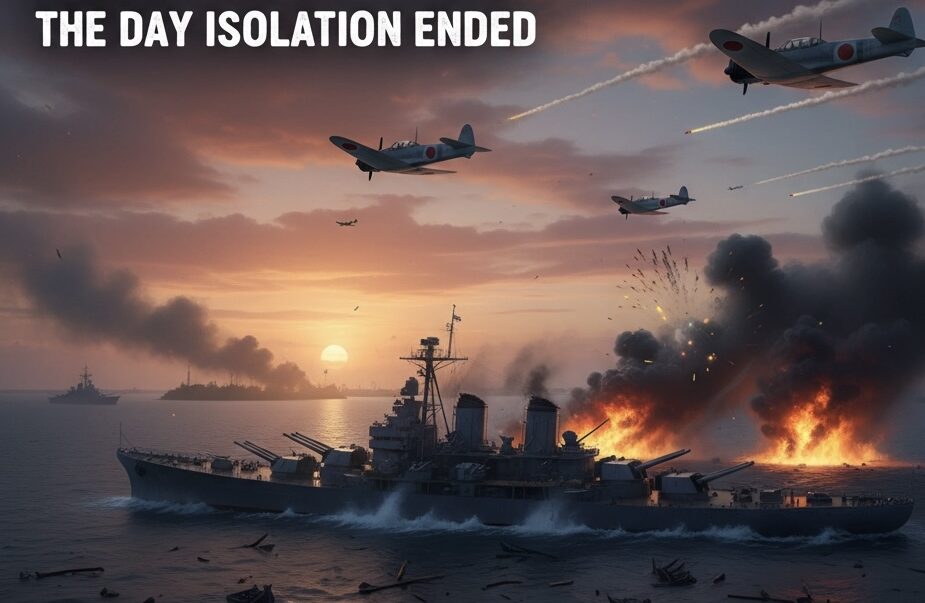

December 7, 1941, was the morning America’s long experiment with isolation died in the flames of Pearl Harbor. In less than two hours, 353 Japanese aircraft transformed the United States from a reluctant observer of global conflict into the world’s most committed belligerent. For a generation of young pilots finishing flight training across the country, including future combat veterans like B.K. Watts, this Sunday morning marked the moment their theoretical preparation became urgent reality.

The Shock Wave That Changed Everything

The attack’s impact rippled far beyond the smoking wreckage in Hawaii’s harbor. Within hours, radio broadcasts carried the news to every corner of America, reaching flight training bases from Randolph, Hicks and Kelly Field. The isolationist movement, which had commanded majority support just days before, collapsed overnight.

Public opinion shifted with stunning speed. Gallup polls showed that before Pearl Harbor, roughly 80% of Americans opposed entering the European war. By December 8, that sentiment had completely reversed. When President Roosevelt asked Congress for a declaration of war against Japan, the vote was nearly unanimous: only one dissenting voice in both houses combined. The era of American neutrality was over, swept away by the reality that oceans could no longer guarantee safety.

For young men in flight training programs across the nation, the abstract possibility of combat suddenly became inevitable. The P-40 fighter aircraft they were learning to fly would soon face real enemies, not practice targets. Training that had seemed routine took on new urgency as instructors pushed cadets through accelerated programs, knowing that every week of preparation could mean the difference between life and death in actual combat.

Two-Front Reality and Strategic Choices

Pearl Harbor created an immediate problem for American war planners: how to fight a global war on two fronts with limited resources. Public rage focused on Japan: the sneak attack demanded revenge in the Pacific. But strategically, military leaders understood that Nazi Germany posed the greater long-term threat to American security and democratic values worldwide.

This tension between emotion and strategy would define America’s war effort. The “Germany First” policy meant that despite Pearl Harbor’s location in the Pacific, the primary American effort would target Hitler’s forces in Europe and North Africa. For pilots like those training alongside B.K. Watts, this strategic decision meant their first combat assignments might take them not to avenge Pearl Harbor directly, but to distant theaters on North African desert airstrips.

The decision also meant that American air power would be stretched thin from the beginning. Fighter squadrons would need to operate across multiple continents, often with minimal support and under conditions their peacetime training had never anticipated.

Mobilization on an Unprecedented Scale

The transformation from peace to total war happened with breathtaking speed. Within weeks of Pearl Harbor, draft boards across the country were calling up hundreds of thousands of young men. Training bases that had operated at peacetime capacity suddenly found themselves overwhelmed with new recruits.

The Army Air Forces, which would soon need to project power across both the Pacific and Atlantic, began a massive expansion program. New airfields appeared across the American landscape, from primary training bases in the South to advanced combat training facilities that would prepare pilots for specific theaters of operation. Aircraft production shifted into high gear, with factories that had built civilian automobiles retooling to produce fighters and bombers.

For flight instructors and cadets already in the training pipeline, this mobilization meant compressed schedules and intensified pressure. The luxury of extended training periods disappeared. Young pilots who might have spent a year mastering their craft in peacetime now had months to prepare for combat against experienced enemy pilots flying proven aircraft.

Human Scale: The Individual Cost of National Transformation

Behind the statistics and strategic decisions were thousands of individual stories: young men who had entered flight training as a career choice now facing the reality of combat duty. At training bases across the country, the atmosphere changed overnight. Conversations shifted from flying technique to combat tactics, from career prospects to survival skills.

The acceleration affected everything. Ground school classes that once moved at a measured pace now covered essential material in compressed timeframes. Flight training hours increased, but so did the pressure to solo quickly and advance through increasingly complex aircraft. Instructors, many of them veterans of World War I or early volunteers who had flown with groups like the Flying Tigers under Claire Chennault, brought new intensity to their teaching.

For pilots completing advanced training, the knowledge that graduation meant immediate assignment to combat units added weight to every lesson. Navigation errors that had once meant a reprimand now could mean death behind enemy lines. Gunnery practice took on life-or-death significance when students realized they would soon face pilots from the veteran air forces of Germany and Japan.

From Training Field to Combat Theater

While America’s industrial and military machine mobilized for global war, individual pilots like B.K. Watts were completing the training that would carry them from American airfields to combat zones around the world. The rapid shift from isolation to total mobilization meant that newly minted pilots would face their first combat experiences not in gradually escalating conflicts, but in major operations planned and executed on a scale America had never attempted.

In the Slipstream follows this transformation from the perspective of one pilot whose journey from flight school to combat operations captures the broader story of how America’s air power evolved from peacetime training programs to global reach. Through B.K. Watts’s experiences, reconstructed from squadron records and personal accounts, the book reveals how the pivot from isolation to global engagement looked from the cockpit rather than the war room, showing the human reality behind America’s emergence as a dominant air power.

Discover more about the story at: https://www.s3publishing.blog/publishing-house-s3/into-the-slipstream/

Leave a Reply